Black Holes: The Universe’s Strangest Mystery

- Aditya Rajesh

- Jul 4

- 3 min read

There’s something out there in the cosmos that defies logic, swallows light, and stretches our understanding of space and time: the black hole. These aren’t just sci-fi monsters—they're very real, very strange, and absolutely fascinating.

At first glance, a black hole seems simple. It’s a region of space where gravity is so strong that nothing—not even light—can escape it. But behind that simple definition lies a cascade of mind-bending ideas. Because black holes aren’t just objects… they’re physical paradoxes that sit at the edge of everything we know about reality.

Black holes begin their story as stars. Not just any stars—massive ones, at least 20 times more massive than our Sun. When such a star runs out of fuel, it can no longer hold itself up against gravity.

The outer layers explode in a supernova, while the core collapses inward—infinitely. What’s left behind is a gravitational singularity: a point of infinite density and zero volume, where the known laws of physics break down. That’s the heart of a black hole.

Surrounding this singularity is the event horizon—a kind of invisible boundary. Once something crosses it, it can never escape. Not a spaceship, not a photon, not even information (probably). To an outside observer, time near the event horizon slows down drastically. If you watched someone fall into a black hole, they'd appear frozen in time, stretched thin by gravity—a phenomenon known as spaghettification.

But that’s just the beginning of the weirdness.

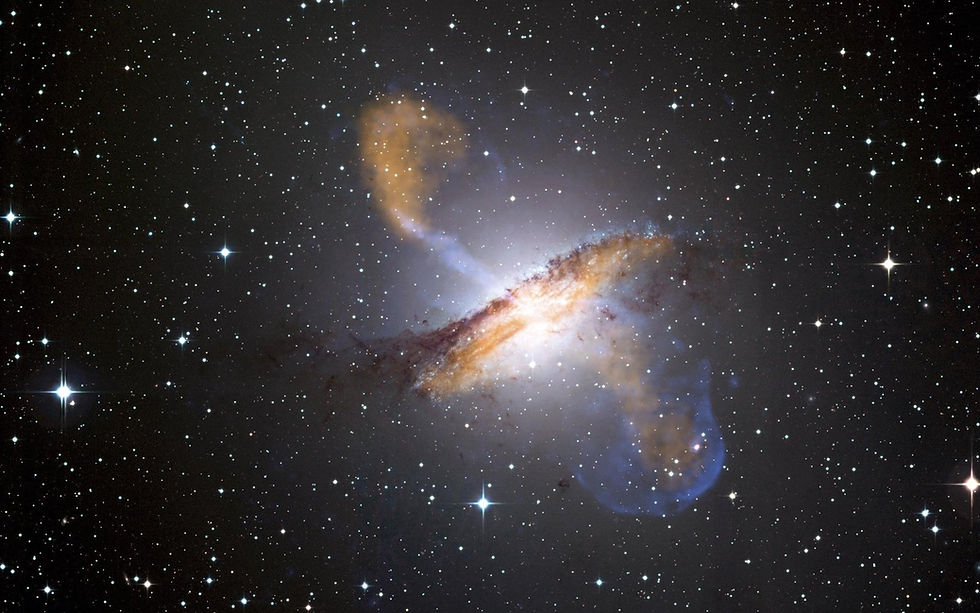

Black holes come in many types. Stellar black holes are the most common, formed from collapsing stars. Then there are supermassive black holes, which live at the centers of galaxies and can weigh billions of times more than our Sun. In fact, the Milky Way itself has one—Sagittarius A*—right at its core. Scientists believe these giants helped shape galaxies during the early universe.

And yes, there are intermediate-mass black holes, and even primordial black holes, which might have formed just after the Big Bang—though we’ve yet to confirm their existence. Theoretically, there could even be miniature black holes no bigger than an atom, if certain quantum conditions were right.

Here’s where it gets deeper.

Black holes aren’t just cosmic vacuums sucking things in randomly. Outside the event horizon, they obey gravity just like any other object. You could orbit a black hole safely—as long as you didn’t get too close. Many black holes also emit powerful jets of energy from their poles, due to magnetic fields and spinning accretion disks of matter swirling around them. Some of these quasars are the brightest objects in the universe, visible across billions of light-years.

And then, there’s Hawking Radiation.

Stephen Hawking proposed that black holes might not be entirely black. Thanks to quantum mechanics, virtual particles constantly pop in and out of existence. If this happens near the event horizon, one particle might fall in while the other escapes—making it look like the black hole is emitting energy. Over vast periods of time, this could cause black holes to slowly evaporate. It was a revolutionary idea: the first bridge between general relativity and quantum theory, two fields that normally don’t get along.

Black holes are more than cosmic oddities. They’re nature’s way of pushing physics to its limits.

Studying them forces us to confront the biggest questions we have:

What is time?

What is space?

Can information truly be lost?

And what happens inside a singularity?

We don’t have all the answers yet—but we’re closer than ever. With gravitational wave detectors like LIGO and Virgo, we’ve already “heard” black holes collide. With the Event Horizon Telescope, we’ve taken the first images of black hole shadows. The veil is lifting.

In the end, black holes are not the end of science—they're the beginning of a new kind of science. A place where the universe stops whispering and starts roaring. A place where our greatest tools—math, observation, theory—still struggle to shine light on the darkest regions of reality.

So the next time you stare into the night sky, know this:

Somewhere out there, in a place beyond time and space, the universe is folding in on itself. And thanks to black holes, we’re learning how.

Comments